The LIBOR Transition, Part 2: Challenges Associated with SOFR

February 5, 2021 •Joseph McCormack, PhD

With contributions by Mark Hutson, PhD

This is the second in a series on the end of the London Inter-Bank Offered Rate (LIBOR), a widely used financial metric that is integral to global finance. In this post, we cover the issues surrounding the primary replacement for LIBOR, named SOFR.

What is SOFR, and how is it calculated?

In part one of our series, we outlined the issues with LIBOR and the steps taken to replace an interest rate that is used within a large number of financial instruments. As defined in part one, LIBOR is the self-reported rate of what banks could borrow from other banks, perceiving what a loan would cost.

|

What’s a repo? A “repo,” or repurchase agreement, involves lending cash and the borrower selling a Treasury bond as collateral. The bank then repurchases (“repos”) the Treasury the next day (plus interest) to close the loan. |

SOFR is the Secure Overnight Financing Rate. It is used because it removes the self-reported aspect and instead evaluates at the rate banks actually lent to one another in the Treasury repo market (see box). By examining the previous day’s rate, SOFR looks at actual costs rather than the perception of costs. The actual calculation is somewhat complicated due to the methodology for weighting transaction volumes, which requires pulling data from three different sources on a number of different transaction types and filtering various U.S. Treasury repo markets.

So what are the limitations of SOFR?

When comparing SOFR to LIBOR, there are two major drawbacks:

- SOFR is only an overnight rate. LIBOR came in many different maturities, from the overnight rate (also called the spot rate) out to maturities of one year. SOFR, based only on the most recent data on Treasury repos, is a spot rate. Thus, longer-term loans need to extrapolate out SOFR to longer maturities. This can be as simple as using a daily compounding rate; however, as some contracts are traditionally based on longer LIBOR maturities, there may be some market frictions around changing to a spot rate; we discuss some of these below.

- SOFR is much more volatile than LIBOR. Using real trades, rather a trimmed mean of bankers’ forecasts, makes SOFR much less stable than LIBOR. Such volatility could add uncertainty or extra risk on common trades or contracts based on risk aversion from getting a higher daily rate.

Why is SOFR more volatile than LIBOR?

|

Why SOFR? To choose a new interest rate, the Alternative Reference Rates Committee, established by the Federal Reserve Board and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, selected SOFR as the best alternative to LIBOR for financial contracts and U.S. dollar derivatives, presenting the truest cost of interbank lending. |

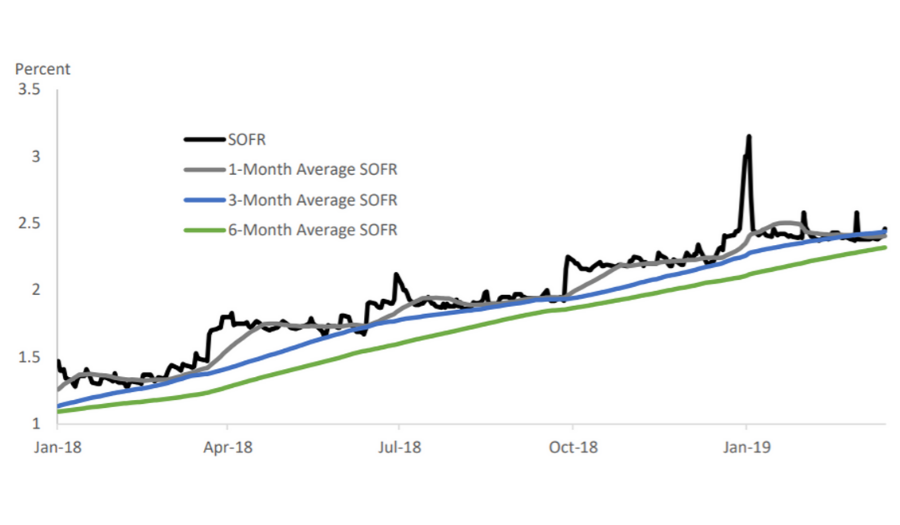

Because SOFR is based on repo transactions, it will inherently be affected by market activity. That is, since these represent actual borrowing rather than rates that a bank projects it could get under LIBOR, there will be more activity-based fluctuations. Because borrowers tend to use repos to provide temporary liquidity to their portfolio, any time with increased (or decreased) needs for liquidity can move SOFR. One such example, seen in Figure 1 below, occurs at the end of fiscal quarters; banks and other entities tend to shore up their balance sheets around reporting times and ensure adequate reserves are on hand.

Broadly, SOFR transaction volumes are regularly around $1 trillion daily. As the number and composition of transactions changes throughout the quarter, rates fluctuate, especially if demand increases well above available supply. For example, Figure 1 shows a particularly large fluctuation in September 2019. This event was triggered by a cash crunch driven by two key factors:

- Corporate tax payments were due on September 16. When corporate tax payments come due, companies withdraw funds from banks and money-market funds, draining the reserves held by each bank.

- Long-term Treasury debts were settled. When Treasury debts come due, the cash is not dispersed until the next business day, which causes an increase of Treasury securities held by primary dealers. These transactions are financed through the repo market, resulting in a further increase in demand for funds.

These two factors drained cash reserves from the system, requiring banks to borrow funds. This mismatch of increased demand and limited supply led to a spike in SOFR.

Figure 1: LIBOR relative to SOFR

Such spikes, then, pose two questions: Does added volatility present a problem? And how do you best control for these fluctuations?

What can be done about SOFR’s volatility?

When designing SOFR, the Alternative Reference Rates Committee (ARRC) viewed the rate’s increased volatility as a potential friction in highly liquid markets, resulting in fewer transactions and potentially higher funding costs. These could lead to both higher costs of capital and lower investment—and potentially a slowdown in global growth. As such, ARRC outlined some potential fixes.

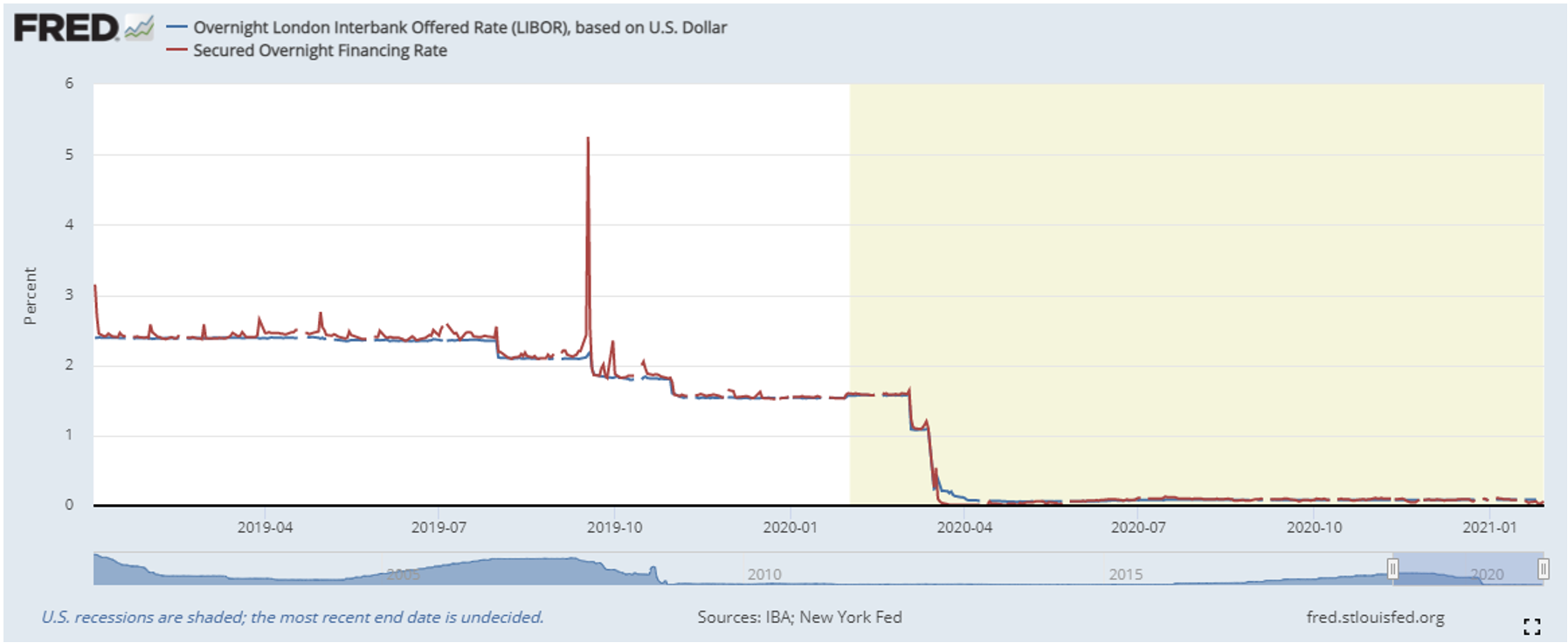

To reduce volatility, ARRC provided a user’s guide that addresses how averaged SOFR can be used to reduce spikes. SOFR is published with overnight, 1-month, 3-month, and 6-month averages. As shown in Figure 2 below, the overnight rate in black shows consistent fluctuations. The longer-term averages remove this short-term variability and instead allow the user to observe trends.

Figure 2: Recent movements in SOFR versus averaged SOFR

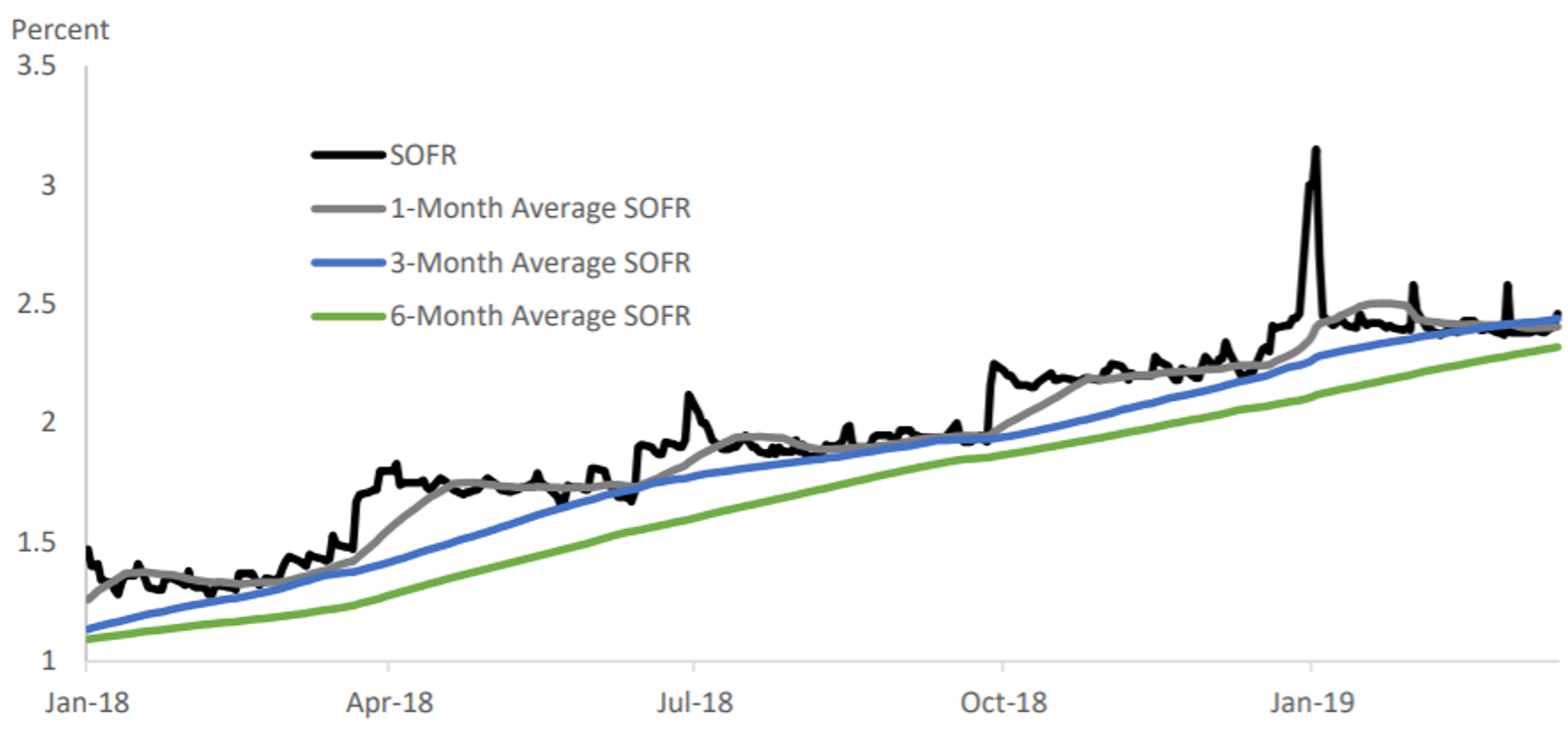

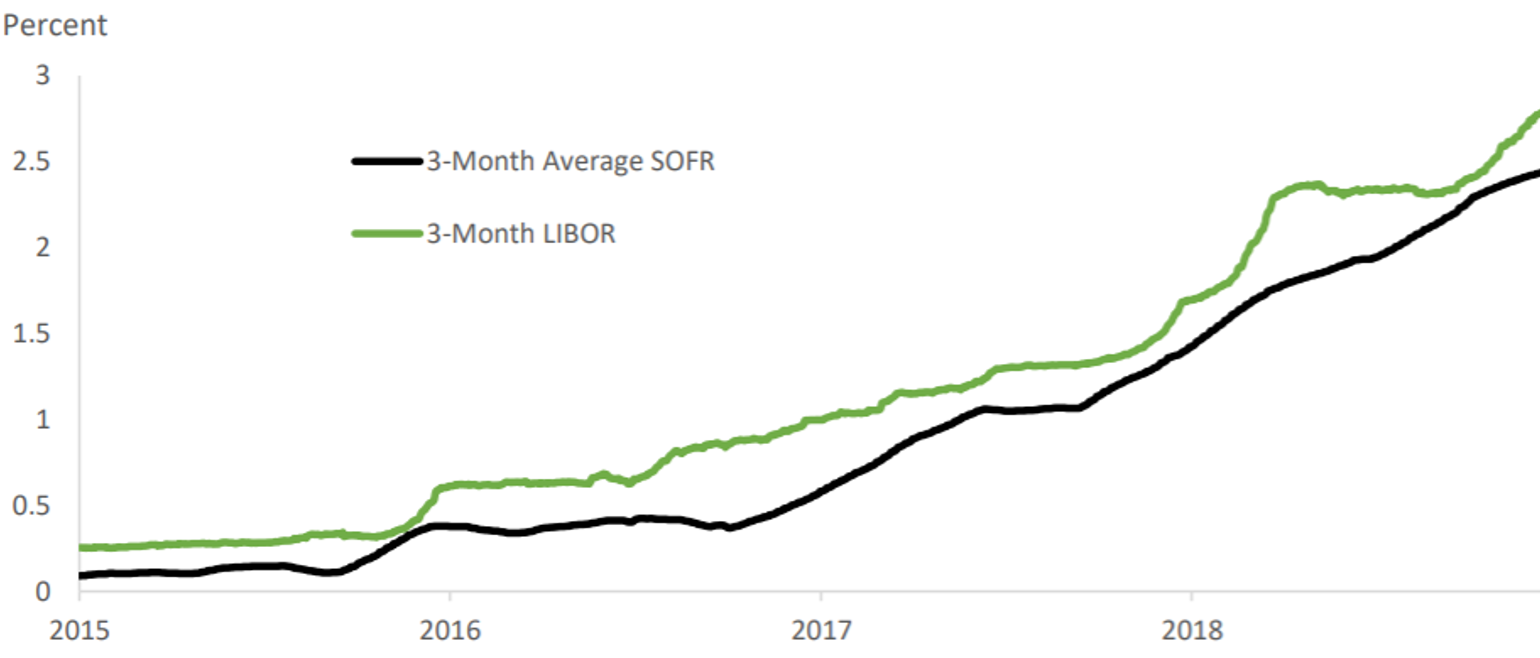

Additionally, Figure 3 shows how the 3-month SOFR average tracks movements in 3-month LIBOR, though SOFR is consistently lower than LIBOR. Thus, banks selecting this smoothing method will eliminate the short-term fluctuations, but will also get different implied costs of the transaction. In this case, because SOFR is consistently below LIBOR, lenders will see lower interest payments under this method.

Figure 3: 3-month average of SOFR versus 3-month LIBOR

Another potential method for getting longer maturities is how banks will extrapolate out interest cost. For example, lenders could employ either simple interest or compound interest:

- Simple interest takes a sum of the individual daily interest amount owed on the principal.

- Compound interest accrues additional interest for the balance not yet paid, applying the daily interest amount not just on the principal but on the unpaid interest as well.

Similarly, investors need to determine the period of time over which to smooth SOFR. Though a 3-month average is less volatile than a 1-month average, the extra two months are much less relevant to today’s rates, with longer smoothing periods adding information to SOFR that is no longer representative of market conditions. When markets turn turbulent, longer smoothing periods are particularly problematic, as SOFR departs farther from actual funding costs. Therefore, reducing volatility could make SOFR less useful as a true gauge of what the rate is designed to capture. In particular, if a variable rate is reset during such a turbulent period, the costs from an “in advance” arrangement could vary significantly from an “in arrears” arrangement, creating very different results.

So what’s next with SOFR?

The increased volatility of SOFR, and the lack of a codified method for longer-term maturity calculations, raise concerns that need to be addressed during the transition. Even as SOFR has been identified as the primary replacement for LIBOR, the switch is not a one-to-one match. As we wrote in part one, “The financial system has embarked on a lengthy process to replace it.” The next steps1 include:

- Decide which average of SOFR to use. Which average do market participants want to employ to smooth out the daily fluctuations observed in SOFR?

- Choose simple or compound interest. How are longer-maturity rates calculated?

- Decide on the period of time that smoothed or longer-maturity SOFR is calculated. Are rates based on trailing averages or the pre-agreement period?

- Set a notice for how payment is due. For the in-arrears arrangement, how long do interested parties have to muster the contract payment if rates are volatile at the end of the reference period? There may be a need for a longer notice of payment.

As we explained in this post, there are a lot of concerns regarding SOFR. In next week’s post, we talk about why the Department of Housing and Urban Development, the Federal Housing Administration, and Ginnie Mae are choosing the Constant Maturity Treasury Index and not switching to SOFR.

This is the second post in a series on the LIBOR transition. Topics include:

- Part 1: The LIBOR transition—SOFR, so good

- Part 3: Why FHA is not using SOFR

- Part 4: The cost of LIBOR—mortgages, damages, and consumer protection

- Part 5: LIBOR and USDA—how removing the LIBOR cap will impact the Farm Service Agency

- Part 6: SOFR at the U.S. Treasury

1 Note that many of these were identified by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/Microsites/arrc/files/2019/Users_Guide_to_SOFR.pdf

Get Updates

Featured Articles

Categories

- affordable housing (12)

- agile (3)

- AI (4)

- budget (3)

- change management (1)

- climate resilience (5)

- cloud computing (2)

- company announcements (15)

- consumer protection (3)

- COVID-19 (7)

- CredInsight (1)

- data analytics (82)

- data science (1)

- executive branch (4)

- fair lending (13)

- federal credit (36)

- federal finance (7)

- federal loans (7)

- federal register (2)

- financial institutions (1)

- Form 5500 (5)

- grants (1)

- healthcare (17)

- impact investing (12)

- infrastructure (13)

- LIBOR (4)

- litigation (8)

- machine learning (2)

- mechanical turk (3)

- mission-oriented finance (7)

- modeling (9)

- mortgage finance (10)

- office culture (26)

- opioid crisis (5)

- Opportunity Finance Network (4)

- opportunity zones (12)

- partnership (15)

- pay equity (5)

- predictive analytics (15)

- press coverage (3)

- program and business modernization (7)

- program evaluation (29)

- racial and social justice (8)

- real estate (2)

- risk management (10)

- rural communities (9)

- series - loan monitoring and AI (4)

- series - transforming federal lending (3)

- strength in numbers series (9)

- summer interns (7)

- taxes (7)

- thought leadership (4)

- white paper (15)