Interest Rate Risk: How Do We Measure and Mitigate It?

July 11, 2023 •Josh Goldberg

With contributions by Michael Easterly, PhD

Regional banks in the United States are troubled. According to a working paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research, the market value of assets in the U.S. banking system is $2 trillion lower than their book value. Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) failed not because it lost too much money on its loans to high-flying start-ups, but due to investments in securities that had the lowest probability of default—Treasury notes and mortgage-backed securities backed by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. When the Federal Reserve started to raise interest rates, the securities that SVB held on its balance sheet lost value, wiping out its capital. Other banks are in a similar predicament, with the same working paper estimating that 1,519 banks do not have enough assets to cover their uninsured depositors, although the authors also note that a scenario where uninsured depositors remove their money from these banks is “likely too extreme.”

Banks make money by borrowing at one rate and lending at another. The difference between the income banks earn on loans and investments and the expense they pay out on deposits and other borrowing is known as net interest income, and the difference between the rates they pay on each is known as net interest margin. But these profits also create a risk. If interest rates rise, banks could be paying a higher rate on the money they borrow while the money they earn on their assets remains stagnant—or their depositors could withdraw their money in search of higher rates.

Asset-Liability Management

Financial institutions typically mitigate this risk through asset-liability management. They match the cash flows from the loans, bonds, and other fixed-income securities they hold against their debts and other obligations. They have several options for doing so: They can borrow at maturities whose required payments match the income they are receiving from their bonds or loans. They can sell bonds that enable them to buy the bonds back before interest rates increase too much. Or they can use interest rate swaps to convert the steady income they receive on their loans to a rate that varies with the current rate.

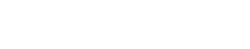

Figure 1: Price-yield relationship for a bond

Source: Adapted from Frank J. Fabozzi, ed. The Handbook of Fixed Income Securities, 7th ed. p. 200.

Financial executives use a measure called duration to measure interest rate risk. Duration is the change in the value of a bond due to a change in the prevailing interest rate. You can see it on the graph in Figure 1 as the slope of the straight line drawn tangent to the price curve at the current price and yield of the bond.

But notice that the line in Figure 1 is curved. That means that the price of the bond will go up more rapidly when interest rates fall than it will decrease when interest rates rise. To measure the change in bond value more precisely, we need to adjust its duration for the curve in the price-yield relationship. This is known as convexity.

In asset-liability management, banks hedge most duration and convexity. They aim to make the durations of their assets and liabilities match as closely as possible. If there is a gap between the two, then they are taking on interest rate risk, and this risk is asymmetric.

As an example, start by measuring the duration of assets and liabilities before hedging. Say the duration of a bank’s assets is 5 and the duration of its liabilities is 2. So assets will reprice faster than liabilities. If interest rates decrease, the assets will increase in price more than liabilities decrease in value. However, if interest rates increase, assets will decrease in value and only be partially offset by the increase in liabilities.

In Figure 2, taken from one of SVB’s investor presentations, we can see from the first line of the text at the bottom the duration in the bank’s assets increasing as time went on. That’s the effect of interest rates. In the second line, hedges are decreasing duration until the third quarter of 2022, when SVB sold all of its hedges (the “n/a” in that row). Unless SVB was increasing the duration of its liabilities, it was taking on more risk.

Figure 2: Duration of Silicon Valley Bank’s portfolio in 2022

![]()

Source: Silicon Valley Bank, "Q4 2022 Financial Highlights." January 19, 2023. https://s201.q4cdn.com/589201576/files/doc_financials/2022/q4/Q4_2022_IR_Presentation_vFINAL.pdf

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac

Asset-liability management can be expensive. With the right incentives in place, however, firms do get it right. In fact, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac each have a duration gap—the difference between the durations on assets and liabilities—close to zero. Their maximum duration in the fourth quarter of 2022 was 0.4 years.

The fact that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac got good at managing interest rate risk is really no surprise when you look at their history. Before the 2008 financial crisis, when they were brought into conservatorship, there was an implicit guarantee that if the government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) got into trouble, the U.S. government would step in to support them. The implicit guarantee turned out to be well founded in 2009, when the government did step in. The result of the implicit guarantee was unusually low debt funding relative to other publicly traded financial institutions. The logical business decision when your cost of funds is your competitive advantage is to grow your balance sheet and make money from the net interest rate spread.

However, this business opportunity to grow your balance sheet would be compromised if interest rates moved in ways that endangered that spread. So the GSEs hired traders and employed techniques to hedge the interest rate risk to very low levels. After all, like banks, they might be expected to take losses when loans went bad because of economic conditions. However, unlike hedge funds, they would not be expected to take losses when bets on interest rates were incorrect. Yet somehow many banks are still operating like hedge funds and making bets on interest rates.

Policy Implications

Should more banks manage their interest rate risk like the GSEs? If so, how can we incentivize this behavior? The answer has implications for bank profitability, regulatory authority, and the overall stability of the financial system.

Get Updates

Featured Articles

Categories

- affordable housing (12)

- agile (3)

- AI (4)

- budget (3)

- change management (1)

- climate resilience (5)

- cloud computing (2)

- company announcements (15)

- consumer protection (3)

- COVID-19 (7)

- CredInsight (1)

- data analytics (82)

- data science (1)

- executive branch (4)

- fair lending (13)

- federal credit (36)

- federal finance (7)

- federal loans (7)

- federal register (2)

- financial institutions (1)

- Form 5500 (5)

- grants (1)

- healthcare (17)

- impact investing (12)

- infrastructure (13)

- LIBOR (4)

- litigation (8)

- machine learning (2)

- mechanical turk (3)

- mission-oriented finance (7)

- modeling (9)

- mortgage finance (10)

- office culture (26)

- opioid crisis (5)

- Opportunity Finance Network (4)

- opportunity zones (12)

- partnership (15)

- pay equity (5)

- predictive analytics (15)

- press coverage (3)

- program and business modernization (7)

- program evaluation (29)

- racial and social justice (8)

- real estate (2)

- risk management (10)

- rural communities (9)

- series - loan monitoring and AI (4)

- series - transforming federal lending (3)

- strength in numbers series (9)

- summer interns (7)

- taxes (7)

- thought leadership (4)

- white paper (15)