IN THE NEWS: The Estate Tax, Part 2 – Reducing Complexity for Heirs

December 15, 2017 •Mark Hutson

We recently covered the idea of unrealized income and why people suddenly see a bunch of income when they die. Today, we’ll discuss how the Estate Tax actually makes life easier for heirs.

Wait, You Mean the Tax Code is Making Life EASIER for People?

Amazingly, the Estate Tax was born as a way to simplify the income tax code. Specifically, the Estate Tax represents a compromise that relieves three major headaches simultaneously:

- The government wants all income to still count as income, eventually.

- People shouldn’t have to do tedious record collections and calculation on behalf of their deceased relatives.

- Society doesn’t need to waste resources on litigating disagreements over estates, especially in cases where administrative records or cost basis are hard to determine.

The Estate Tax was actually an elegant way to accomplish all of the above. It does so in two easy steps:

First, all capital gains are erased through a process called step-up cost basis. Specifically, the purchase price (basis) of all assets are assumed to be purchased at the price they were on the day the owner died. So, in our example of EZ Examples Inc. above, if the stocks were valued at $1,500 on the day the owner died, then the $1,500 value would be the purchase price (basis) for the inheritor. Selling at $1,500, then, would lead to $0 in income (and thus no taxes).

Second, all estates must pay a one-time property tax based on the value of all the holdings. Basically, to make up for not needing to calculate the amount of capital gains on the inherited assets, the deceased ends up paying on the overall value, instead. The EZ Examples Inc. stock is then taxed as $1,500 under the current rate of the Estate Tax, along with Grandpa Bob’s other assets.

In this way, the government is implementing a tradeoff. In exchange for not having to track down and calculate a whole bunch of past values, we’ll instead just tax them on what they are worth at the time of death, whether it is a capital gain or not. The rates are then set such that the revenue from estates should be comparable to what the government would have received from capital gains.

The Estate Tax Today

| Unrealized Gains, as % of Estate |

Break-Even Estate Size |

| 0% | $5,490,000 |

| 25% | $6,057,931 |

| 33% | $6,265,335 |

| 50% | $6,756,923 |

| 55% | $6,916,535 |

| 67% | $7,320,000 |

| 75% | $7,638,261 |

| 100% | $8,784,000 |

I bet a lot of people read the above and started wondering how much they will owe when they die. Well, based on the rates in 2017, the answer is most likely $0. Though you probably own property, the current structure of the Estate Tax only hits 1 out of every 500 people when they die. This is because the current Estate Tax rate has two brackets:

- 0% for the first $5.49 million in property,[1]

- 40% for every dollar over that threshold.

Further, each individual gets the exemption, so married couples effectively can pass on almost $11 million dollars tax-free. Thus, very few people actually end up paying anything. In part, this is because the exemption amount is at the highest level in history.[2] At its peak, the estate tax still only hit roughly 1 out of every 45 estates (in 1998, right at the height of the stock market’s tech boom). Obviously, the amount of benefit that accrues to individuals differs based on what percent of their estate is composed of unrealized capital gains (see table).

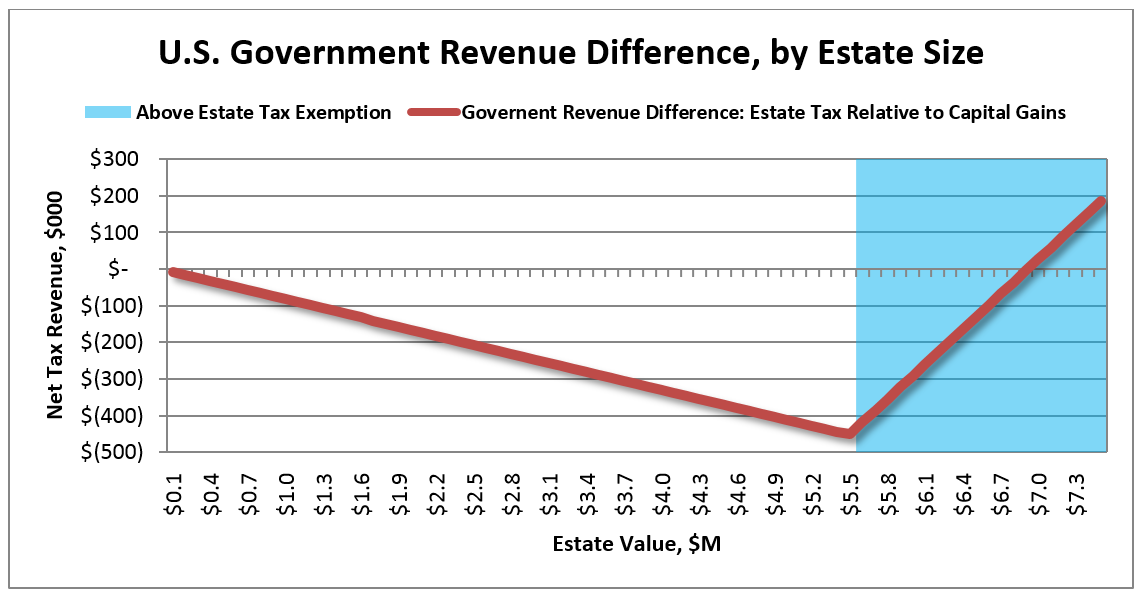

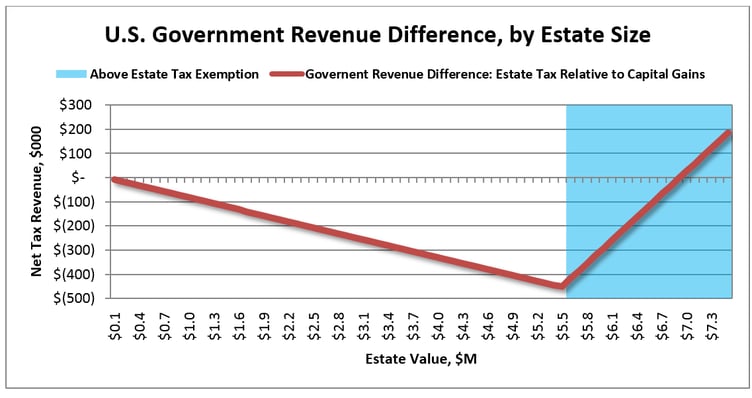

As far as tax revenue is concerned, the Estate Tax is still a major gift to people with a lot of capital gains on the books. Congress[3] and the Treasury estimate that the use of the Estate Tax and step-up cost basis results in lower tax revenue of $62-$71 billion per year. The Federal Reserve Board estimates that roughly 55% of all property in large estates is unrealized capital gains, which implies that the current setup is a net tax break for any estate worth $6.9 million or more (see Figure 1). So, basically, the Estate Tax is only a bad deal for people who die with $7 million or more in assets. Everybody else is either ambivalent or benefits from the Estate Tax.

In SummarY

The Estate Tax really is a form of income tax, in that it exists to replace a certain type income tax: unrealized income at the time of death. It was designed to lessen the administrative burden on heirs, and in practice it has led to much less government revenue (and more money passed along to heirs) than if it had not existed. In its history, it has only been levied on people with significant assets to their name.

So, yes, Virginia, the Estate Tax is an income tax. And, if the proposed tax bill does pass, we’ll be back to discuss the changes and implications from the legislation based on whichever form the final bill takes.

Figure: Government Revenue Differences between Estate Tax and Capital Gains - 55% of Estate

[1] Note that the threshold is indexed to inflation, so it will be larger next year (even if tax reform does not pass).

[2] Well, except technically 2010, when there was no Estate Tax, but also no step-up cost basis. It was a weird year.

[3] Via the Joint Committee on Taxation.

Get Updates

Featured Articles

Categories

- affordable housing (12)

- agile (3)

- AI (4)

- budget (3)

- change management (1)

- climate resilience (5)

- cloud computing (2)

- company announcements (15)

- consumer protection (3)

- COVID-19 (7)

- CredInsight (1)

- data analytics (82)

- data science (1)

- executive branch (4)

- fair lending (13)

- federal credit (36)

- federal finance (7)

- federal loans (7)

- federal register (2)

- financial institutions (1)

- Form 5500 (5)

- grants (1)

- healthcare (17)

- impact investing (12)

- infrastructure (13)

- LIBOR (4)

- litigation (8)

- machine learning (2)

- mechanical turk (3)

- mission-oriented finance (7)

- modeling (9)

- mortgage finance (10)

- office culture (26)

- opioid crisis (5)

- Opportunity Finance Network (4)

- opportunity zones (12)

- partnership (15)

- pay equity (5)

- predictive analytics (15)

- press coverage (3)

- program and business modernization (7)

- program evaluation (29)

- racial and social justice (8)

- real estate (2)

- risk management (10)

- rural communities (9)

- series - loan monitoring and AI (4)

- series - transforming federal lending (3)

- strength in numbers series (9)

- summer interns (7)

- taxes (7)

- thought leadership (4)

- white paper (15)