Building Back Better in Opportunity Zones

December 7, 2021 •Jonathan Ewert, CapZone Impact Investments

With contributions by John Kramer

Disclaimer: The information in this article is for informational purposes only and should not be construed as investment advice or be relied upon to make any investment decisions.

Introduction

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, also known as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Deal (BID), is historic not only for the $1.2 trillion size of the bill, but also for the 5-year length of the authorization. This makes the BID immune to partisan quarrels that could slow the movement of money into transportation infrastructure projects. The federal stage has been set, therefore, for this important legislation to achieve its stated goals. What remains to be seen, however, is precisely how each of the states will achieve those policy goals. Each state, and the voters of each state, must be given the latitude to define and determine success.

One need not look too far for examples of where federal largesse is confounded or even stopped at state capitals. Luckily for policy makers at both the federal and state levels, there is an established bipartisan pathway to direct BID funds to predetermined communities that need it most. Chosen by the governors of each state in 2018, there are 8,766 federally designated Opportunity Zones where BID dollars could flow, each observing not only state goals for economic development, but also federal policy goals for equity.

Roads and Bridges to Economic Opportunity

The Biden administration has a stated goal to focus on racial equity as part of the distribution and grant-making process. Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg has said the country has a duty to reckon with past decisions that may have harmed communities of color, including the unintended consequences of dividing communities instead of linking them together. Pointing to these past decisions in a 2016 speech at the Center for American Progress, then Transportation Secretary Anthony Foxx said the first two decades of the federal interstate system displaced 475,000 families and more than one million people. Many of those people were in communities of color.

Whereas in the 1950s communities of color were targets for displacement, today’s legislative landscape has created multiple overlapping incentives for investment in such communities. Opportunity Zones offer generous tax incentives for investors, particularly when paired with other tax incentives such as the New Markets Tax Credit. During a recent House Committee on Ways and Means hearing on improving transparency and reporting of the Opportunity Zone tax incentive, the Government Accountability Office stated that “on average, the selected tracts had higher poverty and a greater share of non-White populations than eligible, but not selected, tracts. These differences were statistically significant.”

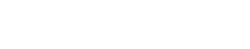

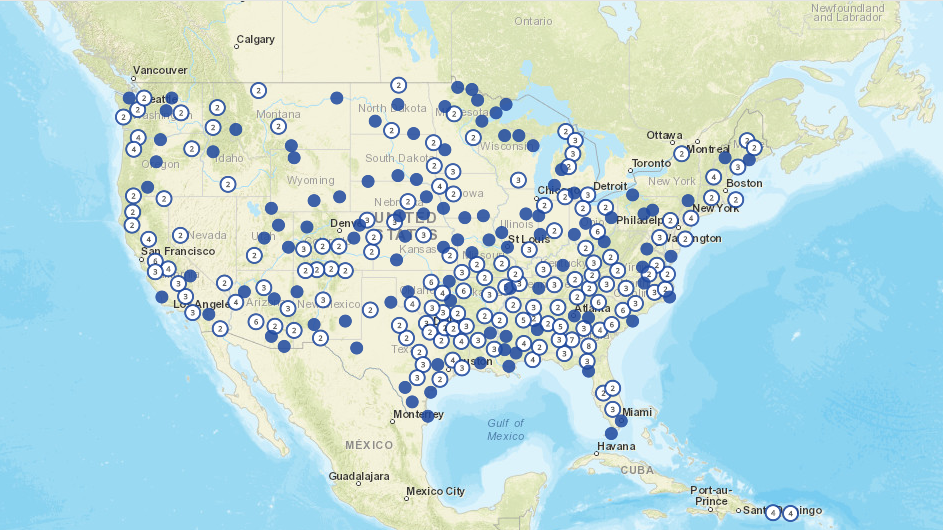

Map of airports in Opportunity Zones. Source: U.S. Department of Transportation

Map of airports in Opportunity Zones. Source: U.S. Department of Transportation

Five Reasons Why Opportunity Zones Work for the BID

In addition to helping solve the racial equity goals of federal policy makers, Opportunity Zones are the perfect mechanism for the directed distribution of federal funds under the BID:

- Opportunity Zones have already been chosen, which accelerates the possible funding flows. No new legislative process or reversible executive order is needed to decide which communities get which infrastructure improvements.

- Opportunity Zones are above politicization. The original legislation and the resultant designation of eligible census tracts in every state and territory were made by both major political parties.

- Opportunity Zones are both urban and rural, just as low-income communities are.

- The Biden administration has already prioritized Opportunity Zones for its infrastructure grant program, commonly called INFRA grants.

- Finally, and perhaps most importantly, Opportunity Zones offer a uniform impact measurement system across disparate geographies, demographics, and investment types.

Prioritizing Opportunity Zones for BID funds would result in a single version of the truth of exactly what kinds of infrastructure improvements actually move the needle for low-income communities.

An Empirical Example: Electric Vehicle Charging

One of the often-overlooked sections of the BID was the creation of the Joint Office of Energy and Transportation. Rather than adding bureaucratic slowdowns, this “bridge” between two distinct departments of the federal government acknowledges the inextricable links between energy policy and transportation policy. Perhaps the best animating factor for this bridge is electric vehicle (EV) charging stations, which have the added benefit of combating climate change.

The BID contains $2.5 billion in charging station grants, as well as a $5 billion companion EV program that specifically includes partnering with private entities to share construction and operating costs for the first 5 years. The Federal Highway Administration’s alternative fuel corridors cover 165,000 miles of our national highway system. While the billions allocated and miles covered sound large, industry estimates say they won’t be enough to achieve the first-ever national network of charging stations. But by placing these charging stations in Opportunity Zones, private capital would impose more financial discipline and have an incentive to amplify the BID funds and achieve the goal of 500,000 charging stations set by the administration by 2030.

To give an example of the private capital that would need to be invested to achieve the administration’s goal, BlackRock is investing $787 million on an EV charging network in Europe that will number only 7,000 charging points. In a similar case to EV charging stations, private investors could partner with local and state transit departments to purchase, charge, and maintain electric and alternative-fuel buses for their fleets in Opportunity Zones, where job creation remains a critical need and where the capital expenditures are likely large.

Milwaukee, Wisconsin, interchange. Photo by Tom Barrett on Unsplash

Milwaukee, Wisconsin, interchange. Photo by Tom Barrett on Unsplash

Looking Forward

The Report Card for America’s Infrastructure from the American Society of Civil Engineers quantifies the urgency and critical need to move federal dollars to improve the nation’s infrastructure. Presidential campaigns for the past 60 years have pointed out the problems, but the solution has remained elusive. Despite the awareness of the problem from Main Street to Pennsylvania Avenue, the KPIs are getting worse: 46,154 of the nation’s bridges are considered structurally deficient, there is a water-main break every two minutes, and an estimated one in five school-aged children lacks a high-speed internet connection.

The Biden administration is the first to find a credible pathway to resolve the nation’s intractable infrastructure problem and the social impacts that have resulted from it. Through a smart legislative process, the two major parties came together to focus on what needed to happen, including a multiyear authorization to make sure that it would. The “last mile” of this groundbreaking legislation depends on where and how states apply the funds and how the BID will work for all taxpayers, not just a few. Prioritizing Opportunity Zones for BID funding is the roadmap for the last mile that everyone can agree on. Financing that last mile through long-term Opportunity Zone equity, especially when coupled with debt from the national Community Development Financial Institution network outlined in our previous post, will ensure community alignment with the policy goals of the BID.

Jonathan Ewert is CEO of CapZone Analytics, a Qualified Opportunity Zone Business that simplifies compliance for Qualified Opportunity Funds and Qualified Opportunity Zone Businesses.

John Kramer is the former Assistant Secretary and Chief Financial Officer of the U.S. Department of Transportation, where he oversaw the department’s annual spending of more than $80 billion.

Get Updates

Featured Articles

Categories

- affordable housing (12)

- agile (3)

- AI (4)

- budget (3)

- change management (1)

- climate resilience (5)

- cloud computing (2)

- company announcements (15)

- consumer protection (3)

- COVID-19 (7)

- CredInsight (1)

- data analytics (82)

- data science (1)

- executive branch (4)

- fair lending (13)

- federal credit (36)

- federal finance (7)

- federal loans (7)

- federal register (2)

- financial institutions (1)

- Form 5500 (5)

- grants (1)

- healthcare (17)

- impact investing (12)

- infrastructure (13)

- LIBOR (4)

- litigation (8)

- machine learning (2)

- mechanical turk (3)

- mission-oriented finance (7)

- modeling (9)

- mortgage finance (10)

- office culture (26)

- opioid crisis (5)

- Opportunity Finance Network (4)

- opportunity zones (12)

- partnership (15)

- pay equity (5)

- predictive analytics (15)

- press coverage (3)

- program and business modernization (7)

- program evaluation (29)

- racial and social justice (8)

- real estate (2)

- risk management (10)

- rural communities (9)

- series - loan monitoring and AI (4)

- series - transforming federal lending (3)

- strength in numbers series (9)

- summer interns (7)

- taxes (7)

- thought leadership (4)

- white paper (15)