Public-Private Partnerships—Opportunities to Advance Infrastructure and Climate Goals

December 2, 2022 •Sarah Cunningham

This article was originally published on November 22, 2022, in Federal Budget IQ, FY23, Issue 2, pp. 7–9.

Over the past year, there have been significant investments in the Nation’s infrastructure. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the CHIPS and Science Act, and most recently the Inflation Reduction Act together have the potential to act as a catalyst to stimulate and modernize the economy. Strong public private partnerships (P3s) that leverage both public and private sector strengths may serve as an effective tool for the Federal government to advance infrastructure and climate goals while reducing government outlays.

There are several potential advantages to the P3 structure. P3s can generate better outcomes for infrastructure investments by allocating certain risks to private entities that are better equipped to manage these over the long term. P3s can facilitate innovation and technology transfer in joint research and development and laboratory initiatives, important to technology companies looking for signposts for investment decisions. Some have also identified P3s for flexible financing opportunities, though Congressional Budget Office (CBO) analysis suggests financing can be more expensive through private channels. Recent legislation has included incentives to explore and expand use of this contractual framework.

The IIJA includes a five-year $100 million effort for the Department of Transportation (DOT) to increase eligible public entities’ capacity to facilitate and evaluate P3s through technical assistance and grants. The IIJA doubled the availability of Private Activity Bonds for surface transportation projects to $30 billion and expanded eligible projects to include broadband and carbon dioxide capture facilities. By August 1, 2024, DOT must submit a report identifying impediments to P3s and proposals to address them. The Biden-Harris Administration identified P3s as part of its COP 27 Climate + effort supporting climate-related financing and USAID support for green bonds through P3s in at least five new countries.

While a promising tool, there are barriers to P3 use that need to be addressed.

What is a public-private partnership (P3)?

Public Private Partnerships, or P3s, are defined by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development as long-term agreements between the government and a private partner, where the private partner delivers and funds public services using a capital asset and shares in the associated risks. P3s can deliver infrastructure projects, such as bridges or toll roads, or service-oriented offerings like hospitals or utilities. Unlike traditional procurement, where the government contracts with a private entity to design, build, or operate the capital asset and yet retains most of the risk, a P3 considers risk over the full investment lifecycle. The P3 value proposition is greater potential efficiency.

Projects have multiple phases—design, build, finance, operate, maintenance, and revitalization. P3s can combine multiple project stages to reduce risk relative to traditional procurement, with greater information and alignment of incentives and risk allocation to the entity best able to manage that risk. Often, the private partner has more capacity for risk management and cost controls.

P3s are structured so that the private entity shares in the risk and cost over the long term. The combination can reduce the timeframe to construct and deliver an asset, or provide the incentives for designs like climate resilient technologies that may have high initial costs but deliver greater value with lower long-term operating costs.

Where have they been used in the past?

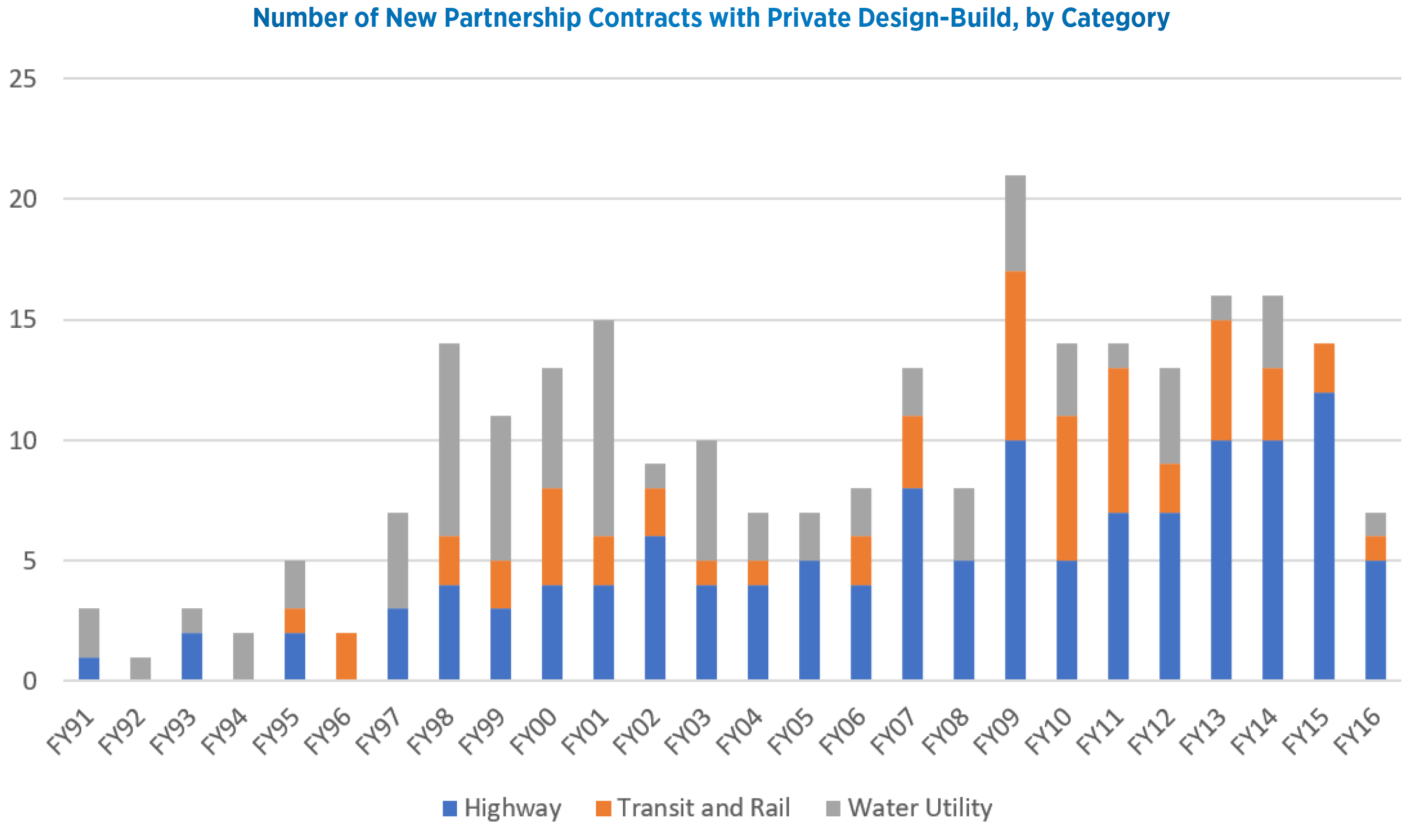

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, states and the federal government began experimenting more with innovative financing and contracting options for transportation projects—giving rise to several P3 projects, including the SR-91 Express Lanes and the South Bay Expressway in California and the Dulles Greenway in Virginia. In 2005, President George W. Bush signed the Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act, A Legacy for Users, or SAFETEA-Lu, giving rise to tax-exempt Private Activity Bonds for transportation and more innovative financing structures. While there was an increase in public-private partnership projects for both transportation and water infrastructure, P3s have not been used broadly at the federal level. A CBO report on Public-Private Partnerships for transportation and water infrastructure found that only 1-3% of transportation and water projects have utilized P3s from the early 1990s to 2016 (see the chart below).

Source: Congressional Budget Office, “Public-Private Partnerships for Transportation and Water Infrastructure”, January 21, 2020.

Source: Congressional Budget Office, “Public-Private Partnerships for Transportation and Water Infrastructure”, January 21, 2020.

P3 Barriers

P3s are complex. The deal structure varies significantly from project to project, and a successful contractual foundation requires detailed planning and analysis to evaluate and identify 1) whether a P3 is appropriate, and 2) if so, what structure best aligns risks to the partner best able to bear that risk. While an intended benefit of a P3 is delivery speed, moving too fast could lead to an unclear contractual foundation—and increased taxpayer risk. Common barriers to public private partnerships include:

- Dedicated Funding Source—P3s require certain funding streams to cover costs over time. At the same time, fees need to be set to recover costs, they also need to be affordable and in line with other policy goals. In cases where significant investment is required to build or maintain infrastructure, user charges needed to offset costs can run counter to equitable access goals. A thorough review is required to understand the revenues a project can generate, and the risks and challenges around project revenue streams.

- Procedural Hurdles—P3s are long-term risk-sharing partnerships between the public and private sector. Legislative and administrative scoring rules related to ownership and control of projects can limit the Federal incentives for P3s. OMB’s Scorekeeping Guidelines state that where the federal government assumes substantial risk, where there is an explicit Government guarantee or third party financing require full budget authority up front, and reflect outlays as the asset is being built or acquired. To counter this risk, a P3 requires strong public sector leadership and public engagement centered on transparency and accountability over the full project lifecycle.

- Legal Barriers—While most states have P3 enabling legislation, some states and local governments lack P3 authority. State statutes vary, limiting the ability for government Public-Private Partnerships—Opportunities to Advance Infrastructure and Climate Goals and private sector entities to scale best practices regionally or nationally. The 2024 DOT report should include proposals to reduce these barriers.

- Regulatory and Permitting—The timelines and uncertainty around regulatory reviews and permitting remain a barrier to private sector involvement in major infrastructure projects. IIJA included a provision addressing this issue. IIIJA codifies the “One Federal Decision” process, setting a two-year time limit for National Environmental Policy Act reviews and permitting.

- Technical Knowledge and Understanding—Scaling P3s from one-off solutions requires broader knowledge and technical expertise that many state, tribal, and local governments currently lack. To address this challenge federal program leaders should identify best practices and provide technical assistance, training, and flexible grant funding to help build state, local, and tribal government capacity for design and implementation of P3 projects.

Future Opportunities for P3s

While not all infrastructure investments are well-suited to a P3 structure, it can be an effective tool for advancing infrastructure investments and achieving broader goals in support of a 21st century economy. The Administration has announced several initiatives as part of the implementation of the IIJA, including several that extend beyond transportation and water initiatives, like the Department of Energy’s Strategy to Secure the Supply Chain for a Robust Clean Energy Transition; the Climate Smart Buildings Initiative that will leverage P3s to modernize federal buildings; and the Presidential Determination to use Defense Production Act authorities to support domestic production of critical minerals and materials. Overall signs are pointing to increased opportunities for P3s, though it will require dedicated federal leadership and support to realize the benefits.

Photo by Mario Sessions on Unsplash

Get Updates

Featured Articles

Categories

- affordable housing (12)

- agile (3)

- AI (4)

- budget (3)

- change management (1)

- climate resilience (5)

- cloud computing (2)

- company announcements (15)

- consumer protection (3)

- COVID-19 (7)

- CredInsight (1)

- data analytics (82)

- data science (1)

- executive branch (4)

- fair lending (13)

- federal credit (36)

- federal finance (7)

- federal loans (7)

- federal register (2)

- financial institutions (1)

- Form 5500 (5)

- grants (1)

- healthcare (17)

- impact investing (12)

- infrastructure (13)

- LIBOR (4)

- litigation (8)

- machine learning (2)

- mechanical turk (3)

- mission-oriented finance (7)

- modeling (9)

- mortgage finance (10)

- office culture (26)

- opioid crisis (5)

- Opportunity Finance Network (4)

- opportunity zones (12)

- partnership (15)

- pay equity (5)

- predictive analytics (15)

- press coverage (3)

- program and business modernization (7)

- program evaluation (29)

- racial and social justice (8)

- real estate (2)

- risk management (10)

- rural communities (9)

- series - loan monitoring and AI (4)

- series - transforming federal lending (3)

- strength in numbers series (9)

- summer interns (7)

- taxes (7)

- thought leadership (4)

- white paper (15)